|

| WI - Cormorant Research Group | The Bulletin - No. 2, September 1996 | Original papers | |

KLEPTOPARASITISM

IN GREAT CORMORANTS Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis

IN INLANDS AREAS OF THE IBERIAN PENINSULA

Juan A. Martín Fernández & Waldemar Ibarra del Pretti

The feeding behaviour of Great Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis was studied during the winters of 1994 and 1995, in three inlands areas of the Iberian Peninsula: gravel-pits in the Jarama River (Madrid), the Tajo River through the city of Talavera (Toledo) and Arroyomolinos Reservoir (Madrid). The wintering population in this zone of Central Spain consisted of 2500 birds censused during January 1995.

In every case, birds move from the communal roosting sites to the feeding areas at dawn, distribute over different pools, reservoirs, gravel-pits and stretches of rivers, fishing in small groups that do not exceed in any case 100 individuals per zone. All kinds of waters show a high grade of eutrophication and productivity, where cormorants fish alone, albeit sometimes in the vicinity of other individuals. The most important prey are Carps Cyprinus carpio, barbels Barbus spp. and Black Bullheads Ictalurus melas (Martín et al. 1994, Blanco et al. 1995).

In the course of the field work, several attempts of stealing of prey by other individuals were observed. This phenomenon only reached significant proportions in one of the feeding areas, the Jarama's gravel-pits. It has been the first time we saw this feeding behaviour, although there are some references of kleptoparisitism between Great Cormorants and Gannets Sula basana in the British Isles (Leach 1982, Tasker & Taylor 1984) and Great Cormorants and White-tailed Eagles Haliaetus albicilla in Sweden (Norén 1981).

In the Jarama area, we observed 27 attempts of prey's thefts by other cormorants and by Yellow-legged Gulls Larus cachinnans too (Table 1). This behaviour could be favoured because the principal prey here, the Black Bullhead, makes the birds employ more time in prey manipulation before swallowing it, due to the presence of some erected bones in both sides of its head and in the spine (first radii of the pectoral and dorsal fins respectively). It is during this fish manipulation period that Great Cormorants are attacked by other individuals, the birds trying to protect themselves by moving to the centre of the pool, diving with the prey to confuse the attacker or starting to fly.

|

In the other feeding areas, we also observed a few attacks, but the cormorants here swallowed their prey more quickly, because they consisted mainly of Carp, barbel and Iberian Nase Chondrostoma polylepis, all of which are species easier to handle.

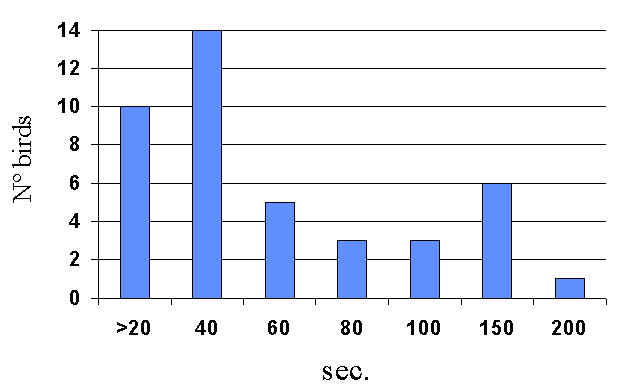

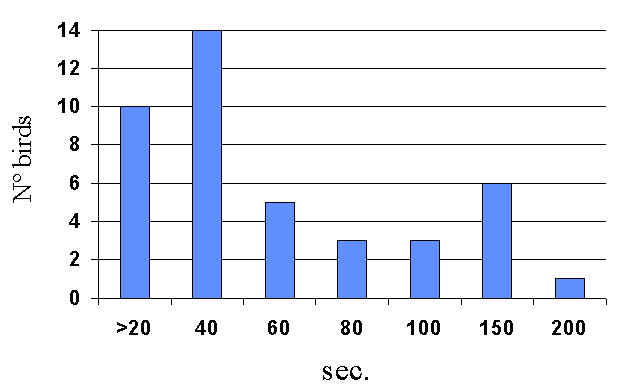

A total of 42 fish manipulations was recorded, the average time used to eat the fish being 51.74 + 43.87 seconds, with a range from 2 to 210 seconds (Fig. 1). In 29% of the occasions, the attackers (all adult individuals) were successful and kept the prey. In a similar percentage of cases, they did not get it, and the fisher swallowed it. In some cases the prey was set free and none of them ate it. The attacking gulls did never achieve the prey, since the cormorants usually submerged with the fish when attacked by gulls, emerging on the surface far away from the place where they were attacked.

The success rate in the intra-specific attacks rose to a 44%, being a rentable strategy and used with relative frequency in those places where Black Bullhead was abundant.

References

Blanco G., Gómez F. & Morato J. 1995. Composición de la dieta y tamaño de presa del Cormorán Grande (Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis) durante la invernada en ríos y graveras del Centro de España. [Diet composition and prey size of the Great Cormorant wintering in rivers and gravelpits of Central Spain]. Ardeola 42: 125-132.

Leach Y.H. 1992. Piracy by cormorants. British Birds 75: 180.

Martín J.A., Ibarra W. & Martín P. 1994. Alimentación del Cormorán Grande Phalacrocorax carbo en zonas de interior de la Península Ibérica durante el invierno. [Diet of Great Cormorants overwintering in inland areas of the Iberian Peninsula]. XII Jornadas Ornitológicas Españolas. Almería. In press.

Norén L. 1981. White-tailed eagles Haliaetus albicilla kleptoparasitizing Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo. Vår Fagelvärld 40: 216.

Tasker M.L. & Taylor A.E. 1984. Gannet robbing Cormorants. British Birds 77: 418.

| fishing bird | attacking bird | nº success |

| young (N = 12) | 9 adult cormorants | 4 |

| 3 gulls | 0 | |

| adult (n = 15) | 8 adult cormorants | 4 |

| 1 young cormorants | 0 | |

| 6 gulls | 0 |

Juan A. Martín Fernández & Waldemar Ibarra del Pretti, P° de Móstoles 43, 1° A, Urb. Parque Coimbra, Móstoles, 28935 Madrid, Spain