| WI - Cormorant Research Group | The Bulletin - No. 2, September 1996 | Original papers | |

REMARKABLE FLEDGLING MORTALITY AT THE LARGEST GREAT CORMORANT Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis COLONY IN THE NETHERLANDS

Stef van Rijn & Maarten Platteeuw

Numbers of breeding Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis around lake IJsselmeer, the Netherlands, have been increasing spectacularly, along with the entire European population, during the 1970s and 1980s (Van Eerden & Gregersen 1995, Lindell et al. 1995). In 1992 this had lead to the presence at Oostvaardersplassen (at the southern edge of this freshwater lake) of the largest known colony of this species in Europe, about 8380 pairs. Afterwards, a crash in breeding numbers was described by Van Eerden & Zijlstra (1995), becoming particularly pronounced after 1993 when an extremely low breeding performance of a mere 0.22 fledglings per occupied nest was recorded. By the year 1994 only a mere 4400 pairs returned to breed, but succeeded again in achieving 0.76 fledglings per nest (Van Eerden & Zijlstra 1995). Then, numbers slowly started to rise once again, with 4940 and 5500 pairs in 1995 and 1996 respectively. The start of the 1996 breeding season seemed rather favourable: many nests held two chicks, 'empty’ nests halfway the breeding season were scarce and chick mortality did not seem excessively high. However, by the time most nestling cormorants were about to fledge and colour-ringing started, indications were obtained that things were not all going right. Quite a considerable number of nests was empty by this time and many (sometimes quite large) chicks were found dead. It was therefore decided to investigate the size of this mortality by carrying out an extensive search for rings immediately after the breeding season.

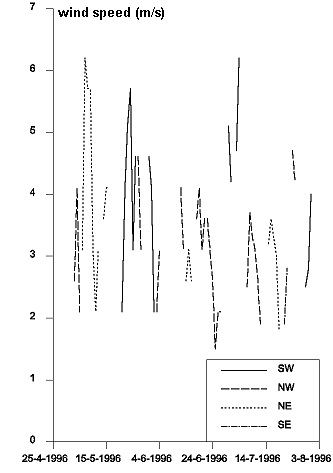

On 13 June and on 31 July 1996, all parts of the Oostvaardersplassen Great Cormorant colony where fledglings were ringed earlier were visited again and controlled for the presence of dead young with rings, either inside or below the nests. Out of a total of 252 birds ringed on 28, 30 and 31 May and 4 and 5 June 1996, a minimum of 57 birds was supposed to have died by this time, suggesting a mortality of well over 20% between the moment of ringing and the moment of fledging (Fig. 1). In order to further pinpoint the time period over which this mortality took place, we compared age-related biometrics of the young during the ringing campaign and among the dead birds found afterwards. The ages of the young, both at the time of ringing and at the time of death, were best estimated by wing length (unpubl. data). Thus it turned out that most of the fledgling mortality took place between 30 and 50 days of age (Fig. 2), e.g. between 25 May and 5 June and between 15 and 25 June, both periods occurring during lessening NW winds and just preceding relatively high SW winds (well over 4 m.s-1; Fig. 3).

|

A

considerable chick mortality had occurred already in the

earlier stages (e.g. before ringing), but there were no

signs that this had been more than usual. Thus breeding

success had been estimated at no less than 1.66 chicks

per nest before ringing, almost twice the maximum value

obtained for the period 1991-94 (Van Eerden &

Zijlstra 1995). The extra 'post-ringing' mortality in the

last decade of June, however, would bring this figure

down to 1.28 fledging young per nest. Levelling off of the numbers of Dutch Great Cormorants seems to continue. One of the natural mechanisms would seem to be low reproductive success as a consequence of (density-dependent) low food attainability. This is most likely to occur when food needs of the young are highest (e.g. at the time of fast growing chicks, cf. Platteeuw et al. 1995). Parents that are barely able to get enough food for themselves at this time of the year (Platteeuw & Van Eerden 1995) can easily be forced to abandon their nest or to lower the load of food brought to the nest by either low fish availability or high energetic costs of foraging (Platteeuw et al. 1995), thus causing the starvation of large numbers of chicks. |

|

It

has been shown that in 1996 the period of peak mortality

of ringed Great Cormorants in the colony coincided with

relatively high NW winds, immediately followed by high

southwesterlies. Particularly these SW winds have been

shown to severely reduce underwater visibility,

particularly on the fishing grounds closest to the colony

(Voslamber & Van Eerden 1991). This might have forced

the birds to engage in longer foraging trips, probably

not compensated for by increased fish intake (cf.

Platteeuw & Van Eerden 1995), and impeded their

capacity to provide enough food for their young. Since

most of the casualties in the colony found turned out to

have been ringed at a lower than average body mass than

would be expected for their respective ages, the

hypothesis of starvation being the main cause of the

mortality seems to be corroborated. In former years, strong winds that occurred after the chicks attaining 25 days of age had less severe effects on young survival (M.R. Van Eerden & M. Zijlstra, unpubl. data). |

References

Lindell L., Mellin M., Musil P., Przybysz J. & Zimmerman H. 1995. Status and population development of breeding Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis of the central European flyway. Ardea 83: 81-92.

Platteeuw M. & Van Eerden M.R. 1995. Time and energy constraints of fishing behaviour in breeding Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis at lake IJsselmeer, The Netherlands. Ardea 83: 223-234.

Platteeuw M., Koffijberg K. & Dubbeldam W. 1995. Growth of Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis chicks in relation to brood size, age ranking and parental fishing effort. Ardea 83: 235-245.

Van Eerden M.R. & Gregersen J. 1995. Long-term changes in the northwest European population of Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis. Ardea 83: 61-79.

Van Eerden M.R. & Zijlstra M. 1995. Recent crash of the IJsselmeer population of Great Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis in The Netherlands. Cormorant Research Group Bulletin No. 1: 27-32.

Voslamber B. & Van Eerden M.R. 1991. The habit of mass flock fishing by Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis at the IJsselmeer, The Netherlands. In: Van Eerden M.R. & Zijlstra M. (eds) Proceedings workshop 1989 on Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo: 182-191. Rijkswaterstaat directorate Flevoland, Lelystad.

Stef van Rijn & Maarten Platteeuw, Rijkswaterstaat RIZA, P.O. Box 17, NL-8200 AA Lelystad, the Netherlands