|

| WI - Cormorant Research Group | The Bulletin - No. 3, December 1998 | Original papers | |

Cormorant management in Bavaria, southern Germany – shooting as a proper management tool?

Thomas Keller1, Andreas von Lindeiner2 & Ulrich Lanz2

1CRG Coordinator Germany, Technische Universität München, Angewandte Zoologie, Block III, D-85350 Freising/Weihenstephan, Germany

2 Landesbund für

Vogelschutz in Bayern e.V.,

Eisvogelweg 1, D-91161 Hilpoltstein, Germany

From 1991 to 1994 a three-year study into the impacts of wintering Great Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis on the fish stocks of a variety of water bodies was conducted in Bavaria, southern Germany (Keller & Vordermeier 1995). Based on the experiences and results of this study, advice was given which was supposed to be an aid in future decision making processes. However this was not intended to replace a check-up of individual cases as they occur. First, it was concluded that the establishment of new breeding colonies in the centres of the Bavarian Carp Cyprinus carpio production areas should not be permitted. Under certain circumstances such control was also thought to be necessary in the vicinity of individual ponds and uncontrolled rivers with Trout Salmo trutta and Grayling Thymallus thymallus populations. Second, as no considerable effect of Great Cormorant predation on fish stocks and fisheries yields could be demonstrated at the studied pre-alpine lakes (Ammersee, Chiemsee), artificial lakes (Altmühlsee, gravel pit Ochsenanger), and large rivers (Danube, Inn, Lech), it was suggested that there was no need for action to protect such fisheries at that time. But, at isolated smaller lakes and gravel pits, and at single important fish wintering sites in backwater areas of rivers considerable impacts on fish stocks seemed possible. In controlled, impounded rivers predation problems also might have arisen among Grayling within the flow sections of lake heads. Thus, a need to use frightening techniques in special cases was seen. Third, due to the specific behaviour of the Grayling, cormorant predation was believed to have a considerable impact on the already small population of this species at the smaller rivers studied (Alz, Maisach). Thus, actions to deter Great Cormorants from sections of uncontrolled rivers suitable for the natural reproduction of Grayling were endorsed. Fourth, to avoid cormorant damage at aquaculture facilities the constant use of a combination of primary non-lethal deterrence measures was recommended under the consideration of legal regulations. If Great Cormorants got used to or did not respond positively to the actions taken, the selective shooting of individuals was suggested to be considered (Keller et al. 1996).

In autumn 1995 a first Bavarian state regulation was issued to prevent anticipated considerable economic damage and to protect native animal species. The shooting of Great Cormorants was made possible in the vicinity of aquaculture facilities, at smaller isolated lakes and gravel pits, at smaller rivers with Grayling populations, at important fish wintering sites in backwater areas of rivers, and at the flow sections of the lake heads of impounded rivers. In every single case a permit had to be issued by the regional state authorities. By the end of the winter 1995/96 179 permits to shoot 2,398 Great Cormorants had been issued and 657 birds had actually been reported shot (after Bavarian Ministry for State Development and Environmental Affairs). As expected, most permits had been applied for at fish ponds (98) and smaller rivers with Grayling populations (56). In opposition to the recommendations made above, the possibilities of using non-lethal scaring techniques were largely ignored.

Then, due to the massive complaints of fisheries lobbyists, a new simplified state regulation went effective in Bavaria in August 1996. Now, shooting was generally allowed within a radius of 100 m next to all water bodies from August 16, 1996 to March 14, 1997. Shooting was not allowed from sunset till one hour before sunrise. In general no permits needed to be issued. The number of birds shot and the date and location of the shooting had to be reported to the regional state authorities by April 4, 1997. This means that no legal control was possible during the actual period of shooting! The legislation had been limited to one year after which it was supposed to be reviewed. A number of exceptions applied. For example, the regulation had not been effective in national parks, nature reserves, wetlands of international importance for swimming and wading birds, and large lakes like the lakes Ammersee, Bodensee, Chiemsee, Starnberg etc. Unfortunately, all those large lakes are located in southern Bavaria, with no stagnant water bodies exempted from the regulation in the northern parts of the state. Additionally, at certain stretches of the rivers Danube, Main, Inn, and Isar the regulation was not effective, too. But this did not mean that there was no shooting in these areas. As it had been the case the year before, permits for shooting Cormorants in those particular areas had to be obtained from the regional state authorities. By the end of the winter 1996/97, when the reports from the hunters came in, a surprise waited for the state conservation authorities. The unexpectedly high number of approx. 6,200 Great Cormorants were reported shot. Within the seven Bavarian regions, the numbers of killed birds were not evenly distributed (Table 1).

Table 1. Number of Cormorants shot in the seven Bavarian regions in the winter 1996/97 (total = 6,068, after Bavarian Ministry for State Development and Environmental Affairs pers. comm.).

| Bavarian Region | Cormorants shot | Remarks |

| Upper Bavaria | 3,330 | --- |

| Lower Bavaria | 722 | --- |

| Swabia | 1,076 | --- |

| Upper Palatinate | 396 | --- |

| Middle Franconia | 465 | --- |

| Upper Franconia | 57 | --- |

| Lower Franconia | 22 | preliminary data |

When looking at these data, it is interesting to note that comparatively low numbers of Great Cormorants were shot in Upper Palatinate and Middle Franconia, although most of the Bavarian Carp ponds are located in these two regions. In contrast, most birds were shot in Upper Bavaria and Swabia, where mostly angling takes place. As no data on the exact locations of the shootings have been released, yet, it can only be speculated that most Great Cormorants were shot at the Grayling and Barbel Barbus barbus sections of the rivers, there.

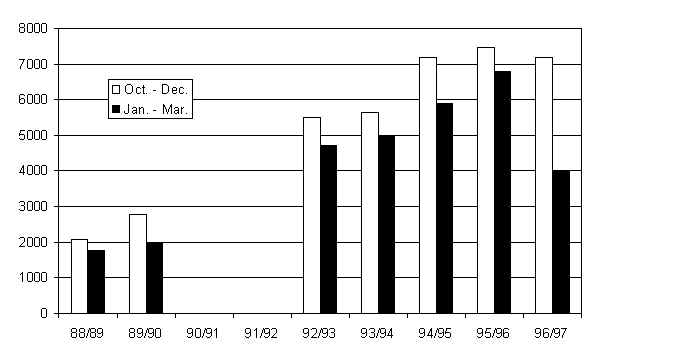

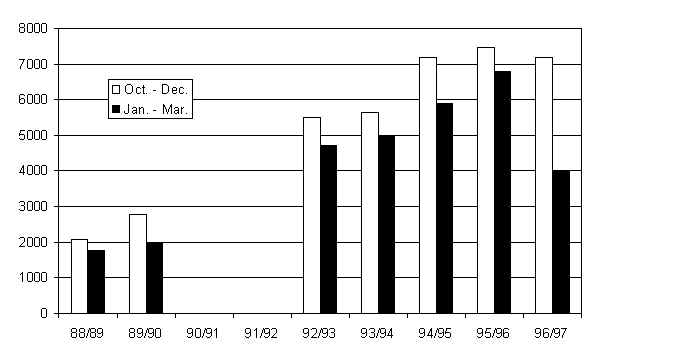

In combination with the numbers of Cormorants it is interesting to see the data of the roost counts of the winter 1996/97 (Table 2). First of all, a rather unusual distribution of Cormorant numbers was found in the course of the winter. From September to December the figures came pretty close to those in the year before. A maximum was registered in November with approx. 9,479 Cormorants. The year before, the maximum had been 8,500 birds. Then, in January 1996 the Cormorant number declined rapidly. Less than 4,000 birds could be found in Bavaria. From January to March the average number of birds was about 2,000 individuals lower than in the winter before (Fig. 1). The overall average from October to March had declined from 7,150 in 1995/96 to 6,127 in 1996/97. The reason for the decline in the Cormorant numbers in the second half of the winter is largely unclear. Two possible explanations are given. One is that the rather cold winter weather with the freezing of most feeding habitats is the most important reason for the low Cormorant numbers. This seems, quite possible as low numbers of wintering Cormorants were also reported from neighbouring German states. On the other hand, also the shooting of 6,068 birds might have reduced the Bavarian wintering Cormorant population.

Table 2. Cormorant numbers at the roosts in Bavaria in the winter 1996/97 (after Lanz 1997).

| Bavarian Region | Sept. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | Apr. | Æ 10-3* |

| Upper Bavaria | 1,194 | 1,486 | 2,043 | 1,868 | 1,649 | 1,302 | 1,285 | 745 | 1,606 |

| Lower Bavaria | 340 | 1,443 | 2,253 | 2,018 | 812 | 1,475 |

735 | 218 | 1,456 |

| Swabia | 97 | 453 | 820 | 912 | 665 | 449 |

755 | 100 | 676 |

| Middle Franconia | 392 | 521 | 645 | 40 | 0 | 132 |

150 | 279 | 248 |

| Upper Franconia | 30 | 13 | 351 | 332 |

140 | 458 | 395 | 21 | 282 |

| Upper Palatinate | 115 | 215 | 781 | 659 | 55 | 167 | 233 | 17 | 352 |

| Lower Franconia | 502 | 1357 | 2,586 | 2,248 | 541 | 1,271 | 1,047 | 306 | 1,508 |

| Total | 3,550 | 5,488 | 9,479 | 8,077 | 3,862 | 5,254 | 4,480 | 1,686 | 6,128 |

* Æ 10-3 = Mean of the months October to March

The number of more than 6,068 Great Cormorants shot means that about as many as the average winter population, which was approx. 6,127 birds (October 1996 to March 1997), and which equals about 65% of the winter maximum of 9,479 birds (November 1996), has been killed. Thus, considerable concern was expressed by Bavarian conservation NGOs. In their opinion the shooting did not scare away the birds from water bodies that were supposed to be protected, but basically killed migrating birds that were rapidly replaced by newly arriving individuals. Especially, as it was not proved that the claimed economic damage could be reduced, and as it was not shown that native fish species benefitted from the shooting, the NGOs demanded the regulation to be reviewed substantially. Most important, they wanted the area that was covered by the regulation to be reduced drastically. This means that in the case of open waters shooting should no longer be permitted at larger rivers at all, but should be restricted to smaller rivers with endangered, native Grayling populations. Shooting should also be forbidden at night roosts in general. Then, no permits should be issued to shoot Great Cormorants in protected areas of any kind in future. Also, as shooting did disturb other species of waterfowl it was claimed that the period of shooting should be reduced to the legal waterfowl hunting period, which is from 15 September to 15 January of each autumn/winter. Finally, at fish rearing facilities more importance should be given to cross-wiring systems that had been tested in Bavaria quite successfully during the last few years.

Then, in August 1997 another one-year state regulation went effective in Bavaria, that did not show any major changes, in spite of all the critics from conservation NGOs. Right now, an NGO complaint against the new regulation is reviewed by the European Commission. This is especially of importance, as the Bavarian way of Great Cormorant management is believed to be a model for all the other German states by fisheries lobbyists and certain politicians.

References

Keller T. & Vordermeier T. 1995. Cormorant Impact Studies in Bavaria (Southern Germany). Corm. Res. Group. Bull. 1: 36-37.

Keller T., Vordermeier T., Von Lukowicz M. & Klein M. 1996. Der Einfluß des Kormorans Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis auf die Fischbestände ausgewählter bayerischer Gewässer unter besonderer Berücksichtigung fischökologischer und fischereiökonomischer Aspekte. Orn. Anz. 35: 1-12.

Lanz U. 1997. Der Winterbestand des Kormorans in Bayern - Ergebnisse der Schlafplatzzählungen 1996/97. Report to the Bavarian Ministry for State Development and Environmental Affairs, 13 pp.

T. Keller, CRG Coordinator Germany, Technische Universität München, Angewandte Zoologie, Block III, D-85350 Freising/Weihenstephan, Germany

A. von Lindeiner & U. Lanz, Landesbund für

Vogelschutz in Bayern e.V.,

Eisvogelweg 1, D-91161 Hilpoltstein, Germany

|