|

| WI - Cormorant Research Group | The Bulletin - No. 3, December 1998 | Original papers | |

SITUATION AND CONSERVATION OF THE EUROPEAN SHAG Phalacrocorax aristotelis IN MEDITERRANEAN SPAIN

Jordi Muntaner & Juan Salvador Aguilar

Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación Dirección Provincial de Baleares, C/ Ciudad de Querétaro s/n, 07007 Palma de Mallorca, Islas Baleares, Spain

This paper is a translated and slightly summarised version of a paper for the Spanish naturalist journal Quercus (October 1995, pp. 20-22), entitled "Situación y conservación del cormorán moñudo del Mediterráneo en España".

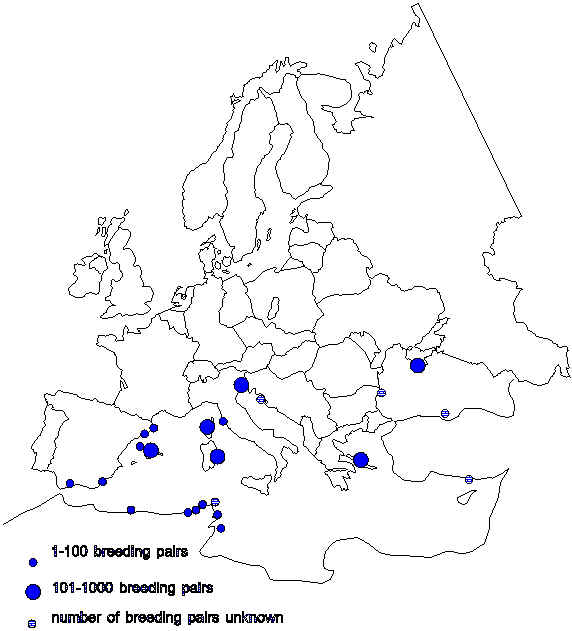

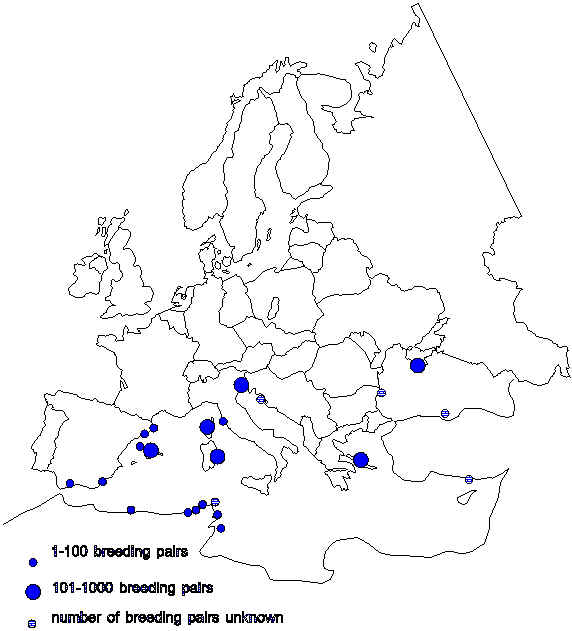

The western Mediterranean area is estimated to hold a population of about 5000-6000 breeding pairs of European Shags Phalacrocorax aristotelis, belonging to an endemic subspecies of the Mediterranean called P. a. desmarestii. Up until now the eastern basin has never been completely censused, while the Black Sea holds less than 1000 pairs. For the entire Mediterranean a total of 10,000 pairs is estimated, distributed mainly along the European coasts (Guyot 1993, Handrinos 1993). The highest concentrations are found along the north-eastern Adriatic Sea and on the island of Sardinia (Italy), with between 1000 and 2000 pairs in each of these regions. Other important nuclei are the Balearics (Spain), Corse (France), the Aegian Sea (Greece) and the Crimean peninsula (Ukraine), with 100-1000 pairs each,

The distribution of the European Shag along the Spanish Mediterranean coast is quite irregular. The most important population is found on the Balearics, which hold an important reproductive nucleus of the species on a Mediterranean scale (Fig. 1). The most recent census, carried out in 1991 (Aguilar 1991, 1992), produced a total of 891 breeding pairs, distributed over five islands as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Numerical development of the breeding population of European Shags Phalacrocorax aristotelis desmarestii in the Balearics, Spain, based on Capella et al. (1986) and Aguilar (1991, 1992).

| Island | Number of breeding pairs in 1986 |

Number of breeding pairs in 1991 |

Percentage of change |

| Mallorca | 995 |

517 |

-48.0 |

| Menorca | 180 |

186 |

+3.3 |

| Ibiza | 105 |

62 |

-40.9 |

| Formentera | 71 |

54 |

-23.9 |

| Cabrera | 95 |

72 |

-24.2 |

| total | 1446 |

891 |

-38.4 |

Some odd pairs also breed on a few sites along the Spanish Mediterranean mainland (Muntaner et al. 1983, Urios et al. 1991, AOCV 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992, Cortés et al. 1980). In the isles of Medes (Gerona), where one or two pairs have been breeding irregularly from at least 1961 onwards (Muntaner et al. 1983, Ferrer et al. 1985), it seems that a small population has now become established and is actually increasing, since up to seven pairs bred in 1993 (pers. comm. J. Sargatal, S. Romero). Elsewhere, e.g. on the cliffs of Garraf (Barcelona), the isles of Columbretes (Castellón) and on the rock of Gibraltar, very small settlements of no more than five pairs have bred in the early 1990s (pers. comm. J. Sargatal, S. Romero, J. Jiménez, A. Sánchez, J.A. Sánchez). Post-breeding concentrations of European Shags in these places, in which immature birds tend to predominate, amount up to 100 birds on the isles of Medes in 1993 (pers. comm. J. Sargatal, S. Romero), up to 388 birds on Columbretes in July 1994 (pers. comm. J. Jiménez, A. Sánchez) and some 200 birds on the cliff coasts of Alicante (AOCV 1992). Most of these birds are undoubtedly of Balearic origin and concern recently fledged juveniles dispersing from the latter area. On the other hand, throughout the year few records are reported from either the Catalan mainland coast or the Levantine coast in the south-east (Ferrer et al. 1986, AOCV 1992) and along the coasts of Málaga and further west the European Shag is even considered a vagrant (Paterson 1990).

|

The European Shag is not a migratory bird. The Mediterranean subspecies in particular should be considered even more sedentary, although individual birds make dispersive movements along the coastlines. The extent of these movements is little known, but birds ringed on Corse have been recovered from Sardinia and the coasts of North-Africa. Shags ringed as chicks in south-eastern Mallorca have been recovered at up to some 150 km from their natal colony, along the north-eastern coastline of the island.

Feeding and reproduction

Shags feed by diving and, if they catch small prey items, are well able to swallow them under water. The average dive lasts for about 40 seconds, while the diving depths have not been measured with any accuracy. In the Balearics many declarations of fishermen have been collected, concerning shags which had drowned accidentally after getting entangled in fishery gear. The majority of fishermen reported maximum diving depths of 15, 20 or even down to 50 metres. It should be taken into account that this type of information tends to be subject to some degree of exaggeration but, anyway, the European Shag is known to be one of the most avid divers of its genus.

Generally, shags feed solitarily, but sometimes they gather together in large flocks attracted by shoals of fish. They are able to cover considerable distances from their roosts for foraging trips (up to 18 km), although in the breeding season the average foraging distance amounts to 7 km with a maximum of about 17 km, as has been determined by radio-transmitters in the Atlantic subspecies (Wanless et al. 1991). It feeds primarily on bottom-dwelling and semi-pelagic fish species. Its diet is rather varied and depends on the availability, consisting mainly of sandeels Ammodytidae, clupeids (sardines and anchovy) and more sparsely blenids and crustaceans. In the Atlantic sandeels and clupeids make up 82% of the diet (Lack 1945). In the Balearics data on food composition only exist for the birds of Cabrera, where rests of Leander serratus, Gymnammodytes cicerellus, Coris julis, Diplodus anularis and other typical littoral fish species have been identified (Araújo et al. 1977). European Shags are evidently rather opportunistic feeders, which adjust their prey choice well to local conditions.

The European Shag nests on inaccessible cliffs, normally inside caves or on ledges. They frequently settle among shrubs growing on the ledges. On islets or isolated sites, where they feel safe, they may nest on quite accessible places, on the ground and among rocks or vegetation. It can be found nesting from sea level up to about a 100 m above sea level.

Typical for this species is the rather low degree of synchronisation in its reproductive behaviour. The reproductive cycle lasts for about three months (30 days of incubation and some 55 days for the chicks to reach fledging). Afterwards the fledged young are still regularly fed by their parents on the water for about three weeks more. Still, while some pairs start breeding as soon as November, others will not do so until June. Most clutches are produced during the months of January and February. Thus, while Mediterranean colonies tend to be occupied for eight or nine months, Atlantic colonies are only attended for on average six months. It has been suggested that this low degree of synchronisation may have evolved as a means to avoid intra-specific competition, a useful purpose in a low-productive area as the Mediterranean. However, the amount of synchronisation seems to be lower in the smaller-sized settlements than in the larger colonies, while the problem of competition would seem to be more acute in the latter (Guyot 1985). Indications have been found that individuals starting earlier do better with respect to reproductive output than conspecifics starting later. This may be due to the fact that late starters are facing more competition than the early birds. In the French Atlantic, Debout (1985) has shown that in European Shags the more experienced individuals tend to breed earlier and occupy better nest sites than birds with less experience.

The reproductive output of European Shags from the Mediterranean has been determined at colonies from Corse, with averages of 1.23 chicks per pair, and from Menorca, where the average is 1.9 chicks per pair (De Pablos & Catxot 1992). Juvenile mortality is mainly concentrated in the first ten days of age.

Causes of mortality

First year birds are evidently the ones that suffer the highest mortality rate in European Shags in the Mediterranean. It averages about 44% during the first year of life and may rise as high as 83% in years of poor food availability. Mortality in adult birds amounts to 14.6% (± 1.1) (Aebischer 1986) and depends less on yearly fluctuations in food availability. The shags may start breeding at two or three years of age, although observations of incubating second year birds, as indicated by the presence of rests of juvenile plumage, are numerous.

In addition to natural mortality European Shags also suffer, both directly and indirectly, increased mortality by human influences. Disturbances in breeding colonies as well as accidental entanglements in fishermen’s gear may cause increased mortality rates. In part of the Balearics (Ibiza, Formentera and adjacent islets) the species even used to be hunted for food. Even dynamite was used for catching the birds (Ribas et al. 1981). Generally, only few fishermen consider the shags to be serious competitors for fish resources. Diet studies on European Shags have shown that they consume mainly fish species of little or no commercial value. Direct persecution has almost completely disappeared.

With respect to unintended by-catches in fishermen’s gear, it has been estimated that a yearly number of between 600 and 1200 European Shags gets entangled and dies. Considering, however, that this cause of death has undoubtedly been affecting the birds for many years, it is highly unlikely that the recent numerical decline can be attributed to it. Fixed underwater gear seems to take the highest toll.

Shags learn rapidly to catch small fish trapped in fishermen’s gear without getting entangled themselves, but many young inexperienced birds may drown in the intent. In the National Park of Cabrera (Mallorca), where a professional and regulated fishery is allowed, the numbers of European Shags drowned in fishermen’s gear have been registered throughout 1991. The exact figures were not yet available at the time this paper was originally published but are likely to be hard to extrapolate for the entire Balearic area, since fishing practices tend to be very different with respect to both timing and use of different gear for different areas in the Balearics.

Population development

The general population development of the Mediterranean European Shags is unknown. It would seem that colonies known from older days have disappeared, like for instance those from Leila (Morocco), Chikli (Tunisia) and some from the Lybian coast. At other sites colonies disappear and reappear. Moreover, numbers in any one colony may vary considerably from one year to another. In Menorca, where the first census was carried out in 1980-83 (Muntaner et al. 1983), the population is rather stable and the different figures found for the censuses of 1991 (Aguilar 1991, 1992, De Pablos y Catxot 1992) are probably attributable to differences in methods.

In the Balearics decreases have been detected on Cabrera (Araújo et al. 1977), which have continued up until today (Capella et al. 1986, Aguilar 1991, 1992). For Menorca a decrease in shag numbers is also suspected (Muntaner & Congost 1979). Among the censuses carried out in 1986 and 1991 all populations except on Menorca have suffered a clear decrease (Table 1). On Mallorca the colony most affected was the one on Cabo Blanco, which passed from 533 pairs in 1986 and 1988 (Muntaner 1989) to 90 in 1991 (Aguilar 1991, 1992) and even less in later years (less than 25 pairs in 1994). The causes of this decline are not exactly known, but the extraction of sand from the sea bottom for beach construction, carried out by the Coastal Direction of the Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Environment, just in front of the colony is likely to have been detimental to sea bottom life. Two more Mallorcan colonies have disappeared altogether, one of which almost certainly as a result of the urbanisation of a nearby beach.

Summarising, the actual population of European Shags in the Spanish Mediterranean amounts to about 900 breeding pairs. Some colonies, like the ones on Cabrera and Cabo Blanco, have been followed for several years, while the information on the other colonies is limited to the census results from 1986 and 1991. This information allows to conclude that the present population, and particularly the one on the Balearics, is suffering an alarming decrease without any clear causes. The colonies on Menorca seem to be the most stable ones. It is urgent that close monitoring of the European Shag on the Balearics should be continued, that the causes of its decline be identified and that adequate measures be taken for its conservation, the more so since its legal status is assessed as "of special interest".

References

Aebischer, N.J. 1986. Retrospective investigation of an ecological disaster in the Shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis): a general method based on long-term marking. J. Anim Ecol. 55: 613-629.

Aguilar, J.S. 1991. Atlas de las aves marinas de Baleares. CAIB-Icona, Unpublished report.

Aguilar, J.S. 1992. Resum de l’atlas d’ocells marins de les Balears. Anuari Ornitològic de les Balears 1991: 17-28. GOB, Palma de Mallorca.

AOCV 1989. Anuario Ornitológico de la Comunidad Valenciana. Estación Ornitológica Albufera-SEO (eds), Valencia.

AOCV 1990. Anuario Ornitológico de la Comunidad Valenciana. Estación Ornitológica Albufera-SEO (eds), Valencia.

AOCV 1991. Anuario Ornitológico de la Comunidad Valenciana. Estación Ornitológica Albufera-SEO (eds), Valencia.

AOCV 1992. Anuario Ornitológico de la Comunidad Valenciana. Estación Ornitológica Albufera-SEO (eds), Valencia.

Araújo, J., J. Muñoz-Cobo & F.J. Purroy 1977. Las rapaces y aves marinas del archipiélago de Cabrera. Naturalia Hispanica 12. Icona, Madrid.

Capella, L., J.L. Jara, J. Mayol, J. Muntaner & M. Pons 1986. The 1986 census of the breeding population of shags in the Balearic Islands. In: MEDMARAVIS & X. Monbailliu (eds) Mediterranean Marine Avifauna. Population Studies and Conservation: 505-508. Springer Verlag, Berlin.

Cortés, J.E., J.C. Finlayson, M.A. Mosquera & E.F.J. García 1980. The birds of Gibraltar. Gibraltar Bookshop, Gibraltar.

Debout, G. 1985. Quelques donnés sur la nidification du Cormoran Huppé (Phalacrocorax aristotelis) à Chausey, Manche. Alauda 53: 161-166.

De Pablos, F. & S. Catxot 1992. El Corbmarí (Phalacrocorax aristotelis desmarestii) a Menorca: recompte de parelles reproductores i paràmetres reproductius. Anuari Ornitològic de les Balears 1991: 13-16. GOB, Palma de Mallorca.

Ferrer, X., S. Filella & J. Xampeny 1985. L’ornitofauna de les illes Medes. In: J. Ros, I. Olivetta & J.M. Gili (eds) Els sistemes naturals de les illes Medes. Arxius de la Secció de Ciències 73. IEC, Barcelona.

Ferrer, X., A. Martínes-Vilalta & J. Muntaner 1986. Fauna dels Països Catalans. Vol. 12: Ocells. Enciclopèdia Catalana, Barcelona.

Guyot, I. 1985. La reproduction du Cormoran Huppé Phalacrocorax aristotelis en Corse. In: Oiseaux marins nicheurs du Midi et de la Corse. Annales du CROP 2, Aix-en-Provence.

Guyot, I. 1993. Breeding distribution and numbers of Shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis desmarestii) in the Mediterranean. In: J.S. Aguilar, X. Monbailliu & A.M. Paterson (eds) Estatus y Conservación de Aves Marinas: 37-45. Actas del II Simposio de Aves Marinas. SEO, Madrid.

Handrinos, G.I. 1993. Midwinter numbers and distribution of cormorants and pygmy cormorants in Greece. In: J.S. Aguilar, X. Monbailliu & A.M. Paterson (eds) Estatus y Conservación de Aves Marinas: 147-159. Actas del II Simposio de Aves Marinas. SEO, Madrid.

Lack, D. 1945. The ecology of closely related species with special reference to the Cormorant and Shag. J. Anim. Ecol. 14: 12-16.

Muntaner, J. 1989. Sobre la gran colonia de Cormorán Moñudo (Phalacrocorax aristotelis) de Cap Blanc (Mallorca). In: C. López-Jurado (ed.) Aves Marinas: 97-104. Actas de la IV Reunión del GIAM. GOB, Palma de Mallorca.

Muntaner, J. & J. Congost 1979. Avifauna de Menorca. Treb. Mus. Zool. Barcelona 1. Barcelona.

Muntaner, J., X. Ferrer & A. Martínez-Vilalta 1983. Atlas dels ocells nidificants de Catalunya i Andorra. Ketrés, Barcelona.

Paterson, A.M. 1990. Aves marinas de Málaga y mar de Alborán. Junta de Andalucía, Agencia del Medio Ambiente, Sevilla.

Ribas, V. et al. 1981. Avifauna d’Eivissa. Col. Nit de Sant Joan 5. Institut d’Estudis Eivissencs, Ibiza.

Uríos, V., J.V. Escobar, R. Pardo & J.A. Gómez 1991. Atlas de las aves nidificantes de la Comunidad Valenciana. Generalitat Valenciana, Conselleria d’Agricultura i Pesca, Valencia.

Wanless, S., M.P. Harris & J.A. Morris 1991. Foraging range and feeding locations of shags (Phalacrocorax aristotelis) during chick rearing. Ibis 133: 30-36.

J. Muntaner & J.S. Aguilar, Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación Dirección Provincial de Baleares, C/ Ciudad de Querétaro s/n, 07007 Palma de Mallorca, Islas Baleares, Spain